Published: : January 28, 2026, 10:39 AM

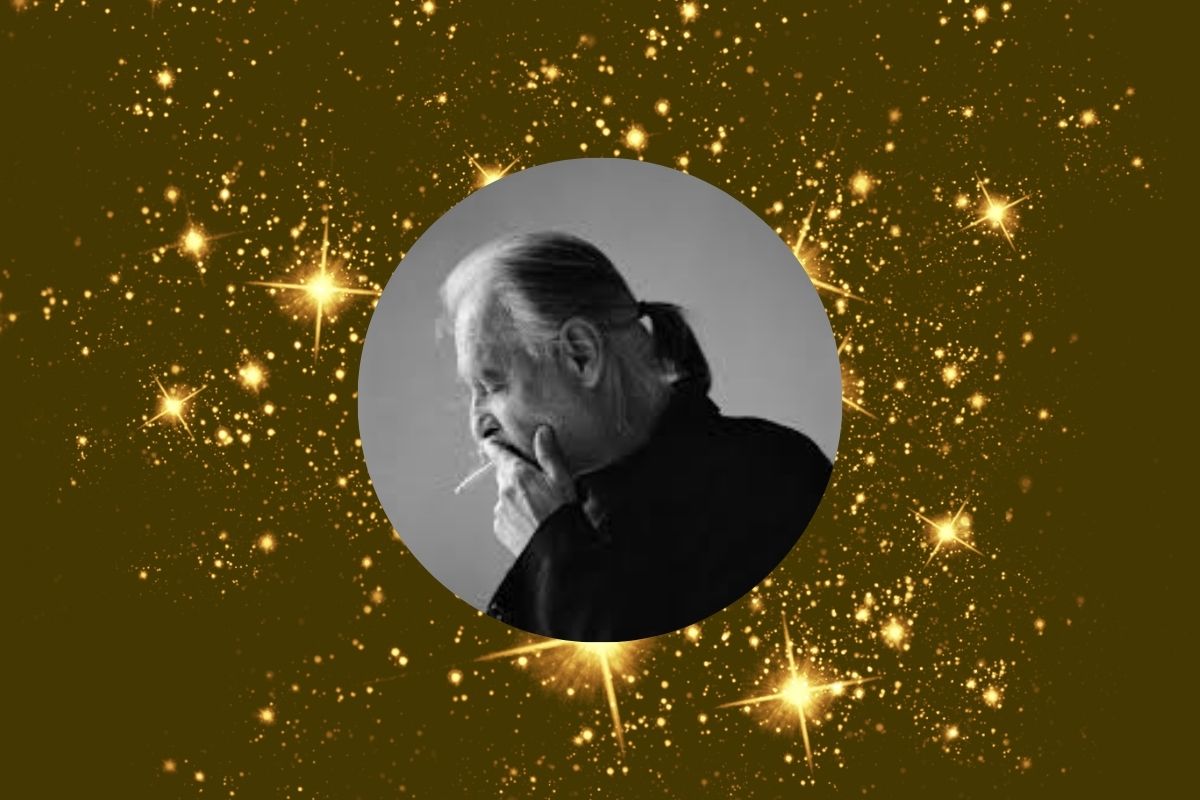

Following the death of Béla Tarr on January 6, cinema has lost one of its most uncompromising moral forces. His films remain as slow, austere monuments, insisting on time, fatigue, and the dignity of looking when nothing seems left to believe in.

Béla Tarr did not make films to explain the world. He made films to stay with it after explanation had failed. With his passing on January 6, his work now fully belongs to history, yet it feels uncannily attuned to the present. Long before collapse became a keyword, the Hungarian filmmaker had already situated cinema in its aftermath. His was not a cinema of crisis, but of what follows crisis, when systems persist only as habits and human beings continue without illusion.

The singularity of Béla Tarr’s cinema lies in its ethical relation to time. His legendary long takes are not aesthetic provocation but moral stance. Time is not shaped for comfort or clarity. It is allowed to unfold, to weigh down on bodies and spaces. Watching one of his films is not a matter of following a plot but of entering a duration that refuses shortcuts. Meaning does not emerge through revelation but through endurance.

This radical vision did not appear fully formed. The filmmaker came to cinema through a deeply social impulse. His first feature, Family Nest, shot in 1978 and released shortly after, is a raw, quasi-documentary portrait of a working-class family crushed by housing shortages and bureaucratic violence in socialist Hungary. Shot in cramped interiors with handheld immediacy, the film bears little trace of the monumental style to come. Yet its ethical core is already present. Béla Tarr looks at people trapped by systems they cannot escape, and he refuses to aestheticize their suffering. From the beginning, cinema for him is a tool of exposure, not consolation.

As his work evolved, realism gave way to abstraction, but the social rage never disappeared. It simply transformed. By the time of Sátántangó, Béla Tarr had abandoned conventional dramaturgy altogether. This seven-hour odyssey through a decaying rural collective does not narrate failure; it inhabits it. The structure itself moves forward and backward, echoing the illusion of progress that endlessly reproduces stagnation. Promises are made, rituals performed, hopes revived, only to collapse again. The camera advances slowly, relentlessly, as if compelled by the same forces that trap the characters.

To describe this cinema as pessimistic is insufficient. Pessimism still implies an alternative, a negative belief in what could have been. Béla Tarr films a world beyond belief. His characters do not expect redemption. They persist because persistence is all that remains. Rain falls endlessly, mud swallows footsteps, wind dominates landscapes with almost metaphysical cruelty. Nature is neither refuge nor threat; it is indifferent, eternal, and overwhelming.

This vision reaches a terrifying clarity in Werckmeister Harmonies. Set in a provincial town destabilized by the arrival of a circus and a mysterious political agitator, the film unfolds like a slow-motion apocalypse. One of its most famous sequences, a single unbroken movement through a hospital, depicts violence not as eruption but as erosion. Order dissolves quietly. Cruelty spreads without resistance. The camera never sensationalizes. It simply refuses to cut away, forcing the viewer to confront the mechanics of collapse.

The visual austerity of Béla Tarr’s work is inseparable from this ethics. Black and white is not nostalgia, nor stylization. It is reduction. By stripping the image of color, the filmmaker removes distraction, leaving only light, shadow, and movement. His collaboration with composer Mihály Víg reinforces this severe economy. The music does not underline emotion; it circles it. Themes repeat, return, insist, creating a sense of temporal imprisonment. The world does not move forward. It revolves around its own exhaustion.

Repetition is, in fact, central to this cinema. Gestures repeat until they lose meaning. Walking, eating, working, waiting. In The Turin Horse, the final film by the Hungarian director, repetition becomes a process of subtraction. Each day resembles the previous one, yet something disappears each time. Light fades. Sound diminishes. Energy drains away. The world does not end in catastrophe but in silence. The film is not about death; it is about what remains when life no longer carries purpose.

That Béla Tarr chose to stop making films after this work is not anecdotal. It is an extension of his cinema. To continue would have meant repeating a gesture emptied of necessity. For him, filmmaking was never production but commitment. When the ethical charge of the act was exhausted, silence became the only coherent response.

After his death, this body of work appears less like an oeuvre than like a single, extended statement. In an era dominated by acceleration, narrative clarity, and emotional efficiency, Béla Tarr’s cinema stands as a refusal. A refusal of speed. A refusal of explanation. A refusal of hope packaged as comfort. His films ask something increasingly rare of spectators: patience, humility, and moral attention.

He did not offer solutions. He did not propose futures. He showed what happens after belief collapses. A man walking endlessly in the rain. A town waiting for meaning. A horse that will no longer move. These images endure not because they are spectacular, but because they are honest.

Béla Tarr is gone. Yet his cinema remains, immobile and demanding, like a final question addressed to those who come after. Not how to save the world, but how long one is willing to look at it once salvation is no longer an option.