Published: : February 17, 2026, 10:00 AM

“I've always remembered something Sanford Meisner, my acting teacher, told us. When you create a character, it's like making a chair, except instead of making someting out of wood, you make it out of yourself. That's the actor's craft - using yourself to create a character.” -Robert Duvall

The death of Robert Duvall on February 15, 2026, at the age of 95, marks the final chapter for one of the most dedicated craftsmen in the history of film. He passed away peacefully at his home in Middleburg, Virginia, surrounded by his family. For those of us who study the art of the moving image, Duvall was more than a famous face; he was a living lesson in how to be human on screen. He didn't just act in movies, he anchored them with a steady, quiet honesty that made everything around him feel more real. To understand Robert Duvall, one must look at his beginnings. Born in San Diego in 1931, he was the son of a Navy Rear Admiral. While his father hoped he would attend the Naval Academy, Duvall admitted he was “terrible at everything but acting.” After serving in the U.S. Army during the Korean War era, he used his GI Bill benefits to move to New York City and enroll in the Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre. It was here, in the mid-1950s, that Duvall shared a cold Manhattan apartment with two other struggling actors: Dustin Hoffman and Gene Hackman. While they worked odd jobs, Duvall was a post office clerk, they spent their nights arguing about film theory and performance. This period was crucial. Under the tutelage of Sanford Meisner, Duvall learned that acting is not about "showing" an emotion; it is about “living truthfully under imaginary circumstances.” This philosophy stayed with him for 70 years.

Duvall’s career was a masterclass in variety and restraint. He famously began in 1962 as Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird. He had no lines, yet his pale, shaking presence told the audience everything they needed to know about fear and innocence. To prepare, he stayed out of the sun for six weeks to look as sickly and reclusive as possible. It was a declaration of his intent: to be essential without being loud. In the 1970s, he became the intellectual "anchor" for some of the greatest films ever made. In Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, he played Tom Hagen, the lawyer for the Corleone family. In a world of volcanic tempers and violence, Duvall’s Hagen was the cool, logical center. He didn't need to shout to be heard; his power came from his posture and his focused, attentive listening. Coppola later remarked that he held formal dinners where the actors had to remain in character, and Duvall’s quiet authority helped solidify the “family” dynamic of the cast. His range was truly staggering. In Apocalypse Now, he shifted gears to play Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore. He made a madman feel terrifyingly normal by treating a beach invasion with the casualness of a Sunday picnic. Later, in the 1989 miniseries Lonesome Dove, he gave us Gus McCrae, a role he considered his personal favorite. He brought a weathered, lived-in dignity to the Western genre, proving that the cowboy was not just a myth, but a man with a heavy heart and a sharp wit.

Beyond acting, Duvall was a filmmaker who cared deeply about the details of life. He was a scholar of regionality, often traveling hundreds of miles to perfect an accent or a walk. This commitment to truth reached its peak in his self-funded masterpiece, The Apostle (1997). When no Hollywood studio would support a serious film about religion, Duvall spent $5 million of his own money to produce it. He wrote, directed, and starred as a flawed Pentecostal preacher. The film remains one of the most honest depictions of faith in cinema history, refusing to mock or simplify its subject. Duvall’s directorial eye was also present in smaller, more intimate works like Angelo My Love (1983), a “docudrama” about New York’s Gypsy community. He was fascinated by real stories and non-professional actors, often blending them with stars to create a texture that felt like documentary footage. He didn't want to make movies that felt like “Hollywood”; he wanted to make movies that felt like neighbors.

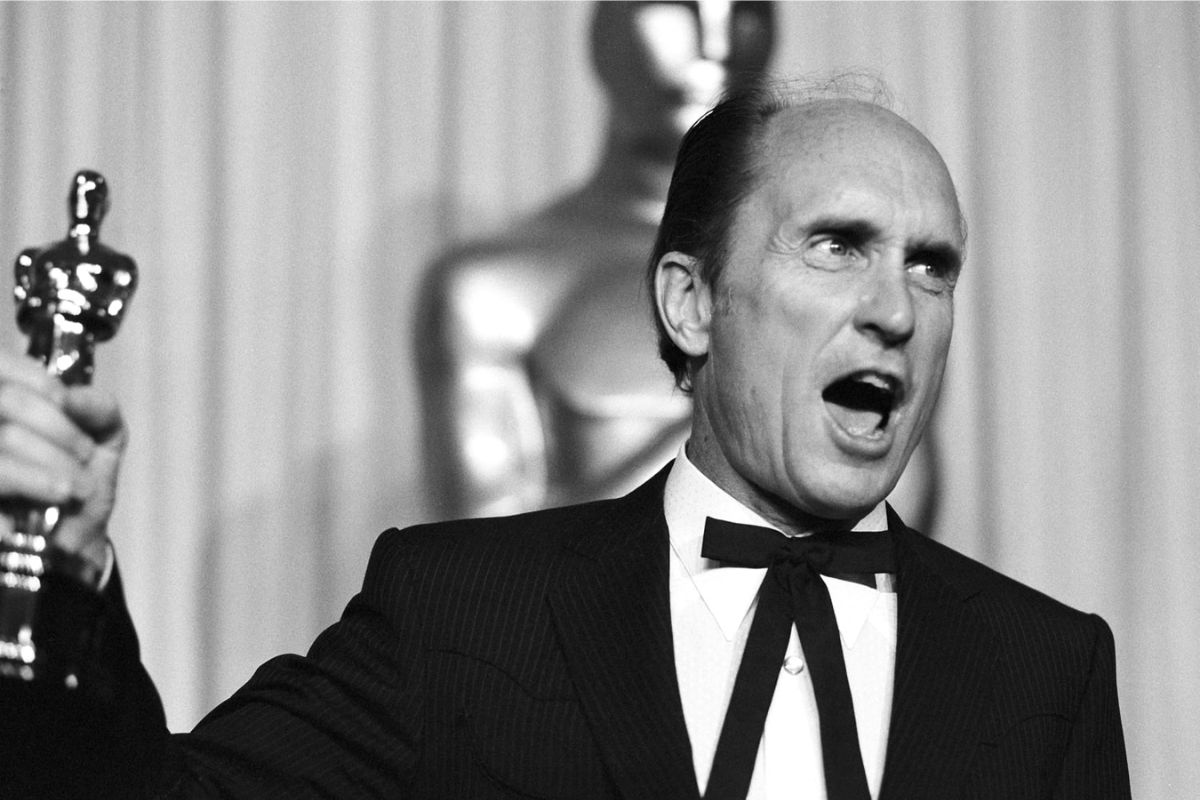

In 1983, Duvall won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in Tender Mercies. He played Mac Sledge, a broken country singer seeking a quiet redemption. He wrote and performed his own songs for the role, once again proving his dedication to authenticity. He didn't use special effects or loud music to show pain; he used his face and his voice. He showed us that every human being, no matter how flawed, has a dignity worth documenting. Even in his 80s and 90s, Duvall continued to work with a sharp mind. In 2014, he became the oldest person ever nominated for Best Supporting Actor for The Judge. He never "retired" because for Duvall, acting was a way of exploring the world. He remained a man of the earth, spending his final years on his farm in Virginia, often seen in the local community as a neighbor rather than a star. Robert Duvall leaves us with a profound legacy. He taught us that great art does not need to be loud to be heard. It only needs to be true. He proved that listening is the most active thing an actor can do, and that character is revealed through behavior rather than dialogue. As we say goodbye to the “last consigliere,” we remember a man who made us believe in every character he played. He didn't just act; he made us see the world with more empathy and clarity.