Published: : February 6, 2026, 08:38 AM

Tagore once said - art has to be beautiful, but, before that, it has to be truthful.

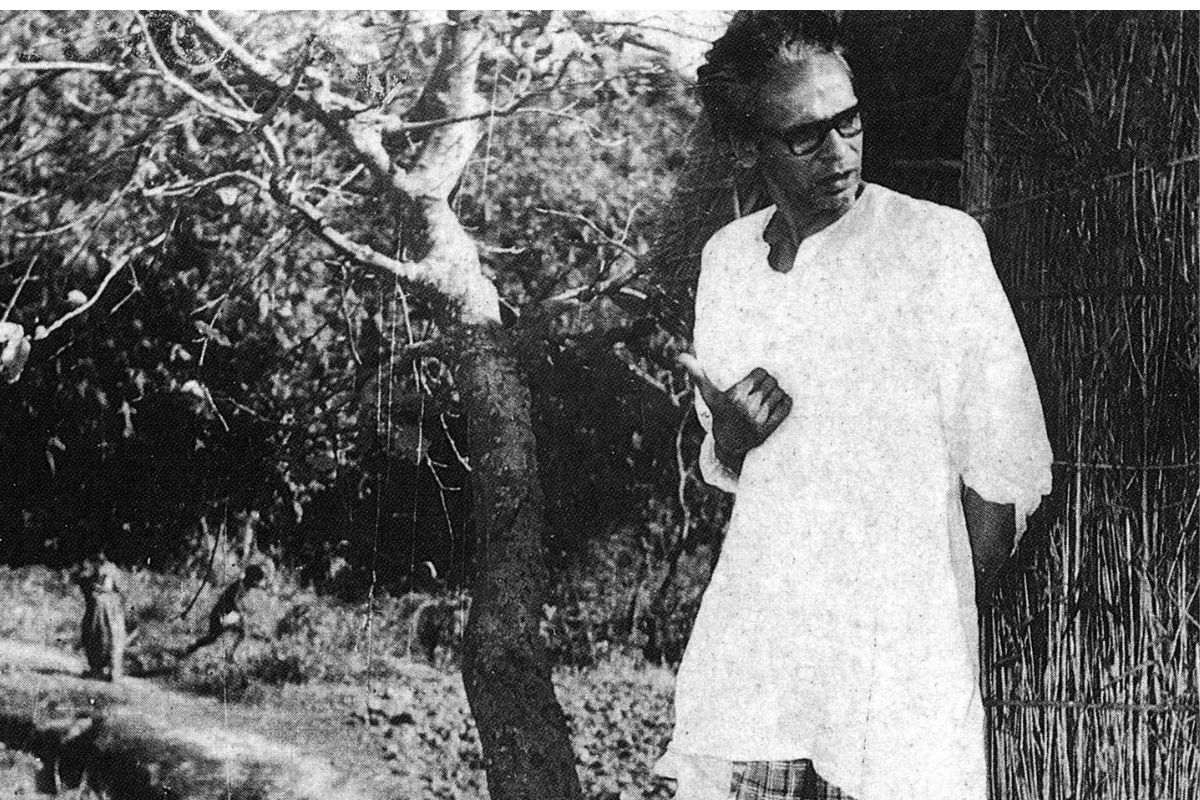

-Ritwik Ghatak

On February 6, 1976, Ritwik Kumar Ghatak passed away in a state hospital in Kolkata. He was only 51 years old, his body exhausted by tuberculosis and chronic alcoholism. For decades, he was remembered as the ‘tragic’ outlier of Indian cinema, a man whose debut feature, Nagarik (1952), remained unreleased for twenty-five years until after his death. Yet, fifty years later, the global cinematic landscape has shifted. We no longer view Ghatak as a failed artist, but as a prophet whose ‘cinema of rootlessness’ serves as a universal mirror for our modern, fractured world. The primary reason we still need Ghatak in 2026 is that his central trauma, the 1947 Partition of Bengal has become a global archetype. While his contemporary Satyajit Ray sought a poised, classical humanism, Ghatak refused to look away from the wound of the ‘Great Betrayal.’ He understood that when a land is divided, something in the human spirit is permanently severed. In an era of mass migration and hardening borders, Ghatak’s obsession with ‘the loss of home’ is no longer a regional concern; it is the definitive story of our time.

Ghatak’s necessity is most evident in his ‘Partition Trilogy’: Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar and Subarnarekha. These films do not just tell stories; they document the psychological disintegration of a people. In Meghe Dhaka Tara, the protagonist Nita represents the ‘Great Mother’ archetype, a nurturing force consumed by the very family she sustains. Her final cry, ‘Dada, ami banchte chai!’ (Brother, I want to live!), is not merely the plea of a dying woman; it is the roar of a culture refusing to be erased. Ghatak used the specific geography of refugee camps to tell a story that reached the scale of Greek or Sanskrit tragedy.

Ghatak famously declared, ‘1 am not an artiste, nor am I a cinema artiste. Cinema is no art form to me. It is only a means to the end of serving my people.’ This was a rejection of cinema as mere entertainment. Coming from a background in the Indian People's Theatre Association (IPTA), he viewed the camera as a ‘bomb’ to be used against social complacency. Influenced by Bertolt Brecht’s ‘Epic Theatre,’ he sought to keep his audience intellectually awake rather than emotionally sedated.

His style was deliberately ‘abrasive.’ He used wide-angle lenses to distort space, placing human faces in the extreme foreground against vast, indifferent landscapes. This visual tension symbolized the individual’s struggle against the crushing weight of history. His sound design was equally radical; he decoupled sound from image to create psychological depth, such as the lashing whip sound used in Meghe Dhaka Tara to signify internal emotional pain. These were not errors of a jinxed director, but deliberate choices of a master who understood the grammar of cinema only to break it for a higher truth.

Ghatak’s legacy lives on through his brief but fiery tenure as the Vice-Principal of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII). He taught his students to be ‘unmechanical,’ urging them to find their own roots before touching the camera lens. He mentored the pioneers of the ‘Indian New Wave,’ teaching them that cinema must be a social instrument. Today, the intellectual rigor found in the works of his students is the true testament to his teaching. He famously argued that a filmmaker must be deeply concerned with their surroundings and the society they inhabit.

We need Ghatak today because he represents intellectual honesty. In his final film, Jukti Takko Aar Gappo, he played the protagonist Nilkantha, a wandering intellectual who admits, ‘I am burning, everyone is burning, the universe is burning.’ In a world of curated images and filtered realities, Ghatak’s work remains raw, messy, and deeply human. He reminds us that art must be grounded in the soil and that memory is the ultimate form of resistance. Fifty years after his death, we are finally ready to listen to what he was trying to tell us all along.