Published: : November 17, 2025, 11:49 AM

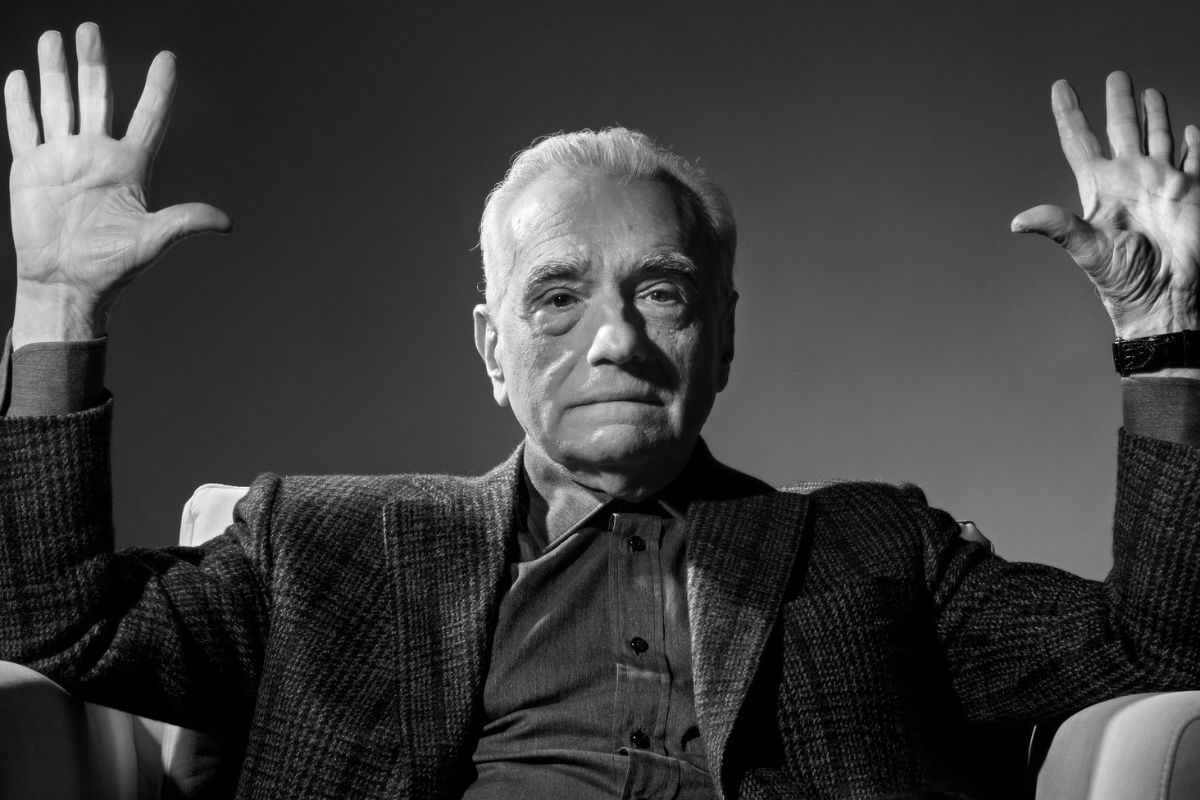

Martin Scorsese built a cinematic kingdom out of his own obsessions: faith, guilt, violence, memory, masculinity. His films feel like living worlds. But as much as he’s a towering artist, he’s also a director whose moral universe has its blind spots. The best criticism of him isn’t just noting his brilliance, it’s calling out where that brilliance stops short.

Scorsese’s cinema is morally intense, and technically relentless. In his work, violence isn’t just spectacle, it is confession, a way for characters to purge, to punish, to understand themselves. In a 2024 study, Boiko et al. describe his films as a kind of “auteur manifesto,” where stylistic elements (editing, framing, camera movement) are deeply bound to his ethical concerns.[i]

This manifesto-like quality gives his films a moral weight. His characters don’t just fight. They march through their own conscience. His camera isn’t neutral, it is in constant tension with the world it portrays.

But the world according to Scorsese has a glaring gender problem. Criticism of his treatment (or neglect) of female characters has been a recurring discussion. In a 2019 press conference, Scorsese responded to a question on the lack of female protagonists by saying it was “not even a valid point.” He defended himself: “If the story doesn’t call for it … it’s a waste of everybody’s time.”[ii]

This justification falls short when you examine films like The Irishman: Anna Paquin’s character, Peggy Sheeran, delivers just a single line. Scorsese later explained he and screenwriter Steven Zaillian considered expanding her role, but “decided against it … she doesn’t have to say anything.” [iii] That might sound poetic, but it raises a critical question: when silence is the only given to a woman’s character, is she being fully seen, or merely used as a symbol or observer?

Nicole Kidman recently voiced this concern, saying: “I want to work with Scorsese — if he does a film with women.”[iv] Her comment underscores a larger frustration among actors and critics: Scorsese’s world often feels like a “men’s club,” powerful and immersive, but limited in its view of women.

Scorsese has claimed that under-represented female voices in his films don’t need to speak loudly to matter. He defended Anna Paquin’s silent role in The Irishman, saying that her absence of dialogue speaks volumes: “She saw what he did … She knows what he’s capable of.”[v] But critics argue that silence can’t always stand in for depth. When women exist as moral compasses or witnesses rather than as fully realized subjects, the balance of power in his storytelling remains skewed.

There’s also the question of inclusivity beyond gender. In Killers of the Flower Moon, which tackles the Osage murders, some Native critics have argued that the film centers white perspectives too much, leaving Indigenous individuals underwritten.[vi] If Scorsese’s moral world is expansive, it still risks leaving out many lives that deserve not just presence, but full narrative dignity.

One more tension: Scorsese’s formal brilliance sometimes borders on indulgence. His films deliver violence with grace, the camera lingers, the editing breathes, the rhythm seduces. But when violence is aestheticized, do we risk glamour? Is the brutality becoming beauty, and is that morally dangerous?

Critics such as Richard Brody have pointed out how films like Raging Bull present violence not just as a character trait but as a ritual of power, even of desire.[vii] There’s an argument that in some of his work, the spectacle of suffering becomes part of the performance, which complicates his moral claims.

Scorsese’s commitment to film preservation is undeniably noble. He sees cinema as memory, a way to safeguard cultural and moral history. But there’s another side: his very dedication to “classic” cinema can feel conservative. In defending narrative, character-driven films, he sometimes frames modern or commercial cinema (like superhero films) as threats, which raises a question: is his fight for “cinema as art” also an elitist resistance to change?

The world according to Martin Scorsese is magnetic: it’s packed with moral interrogation, unforgettable characters, and cinematic bravado. But it’s not a flawless world. His neglect of strong female perspectives, occasional romanticization of violence, and a sometimes nostalgic conservatism in his cinematic ideals compel us to critique as fiercely as we praise.

[i] Boiko, Olha; Batalina, Khrystyna; Stepanenko, Kateryna; Danyliuk, Volodymyr; Zaporozhchenko, Vitalii. “The manifesto in Martin Scorsese’s auteur films.” Scientific Herald of Uzhhorod University. Available at: https://physics.uz.ua/en/journals/issue-55-2024/the-manifesto-in-martin-scorsese-s-auteur-films.

[iii] https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/martin-scorsese-the-irishman-anna-paquin-female-character-one-line-a9178836.html

[iv] https://www.nme.com/news/film/nicole-kidman-subtly-calls-out-martin-scorsese-not-enough-films-women-3812704

[v] https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/martin-scorsese-interview-irishman-robert-de-niro-al-pacino-leonardo-dicaprio-marvel-netflix-a9276891.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com